Editor’s Note:

At Grief Dialogues, we believe art helps us carry what grief leaves behind. Photographer and author Stacy Bass shows us how images and words can preserve love, memory, and light. Her journey from Speak, Memory to her forthcoming memoir Lightkeeper reminds us that even in loss, creativity can sustain us and connect us to one another. Read my interview with Stacy Bass here.

—Elizabeth Coplan

Preface

I’m afraid I am beginning to forget.

I always thought I had a great memory. I remember lots of things with little meaning. Like my childhood home phone number: 226-6634. And the number for my private line from my teenage years: 226-9889. The strawberry yogurt pie that my mom always made and how delicious it was a day later, after it started to decompose a bit. How the graham cracker crust absorbed all that flavor to create a thick and creamy paste I found irresistible.

I also remember little things with lots of meaning. What it felt like when my ten-year-old camp boyfriend, Kenny Salk, put his arm around me during a screening of Star Wars on a humid, rainy day in July in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire. How the fragrance from the lilac trees in our yard made me feel safe. The sensational electricity that coursed through my entire body when I held my husband Howie’s hand for the first time. These memories are broad and deep and teeming with life—overflowing with emotion and punctuated with rich detail.

When I was a freshman in college, I took Psych 101. One day in the enormous and packed lecture hall, the professor asked students to volunteer their earliest memories. Emboldened, I raised my hand and recalled my first birthday. My Uncle Sid, who then worked as a furrier, brought me a tiny, white fur jacket as a gift. I opened my presents in my grandparents’ den while I sat on a delicate, pink upholstered rocking chair with white wire detailing. The professor audibly chuckled as I described the memory. He assured me (and the rest of the class) that this was impossible and that I only thought I remembered that moment. I had no doubt seen a photograph, he conjectured, that I now confused as a memory. And most assuredly, he was right.

I realized then how vital photographs are and will always be in recon- structing and reinforcing our memories. That moment also gave me a glimpse into how lost I might feel without those images to draw on. I am sure I didn’t realize it then, but this formative experience led to my eventual passion

and profession as a photographer. Making photographs—moments frozen in time—has become indispensable to who I am.

Still, I am afraid I am beginning to forget.

I can access the photographs in my scrapbooks and the slides stacked in the old Kodak carousel that highlight slices (slivers, really) of my life, but so much is falling away now. I can’t really remember the sound of Dad’s voice or his occasional and subtle lisp anymore. The intonation and cadence are there, though dissolving, but the sound, the tone, the timbre—they’re largely gone. My grief only compounds the sense of urgency I feel when searching or grasping for a memory. They have become all the more crucial because I don’t get to make new memories with Mom or Dad.

I now realize that photographs are merely starting points. Not proof per se, but a portal into the memory itself, which is refracted even more by the rela- tionships they chronicle and the life that existed outside their borders. Maybe words can fill in and expound upon the pixels just outside the frame? Maybe a book like this can breathe new life into old photos and reconstruct the multi- dimensional beings who were captured and flattened, for an instant, under the sheen of the photographic paper?

In my early twenties, I aspired not to “take” pictures but to “make” them, to examine all that lay beneath them. Susan Sontag’s words from On Pho- tography filled my mind: “The photographer was thought to be an acute but non-interfering observer—a scribe, not a poet. But as people quickly discov- ered that nobody takes the same picture of the same thing, the supposition that cameras furnish an impersonal objective image yielded to the fact that photographs are evidence not only of what’s there but of what an individual (his/her mind and his/her eyes) sees; not just a record of the world but an evaluation of [it].”

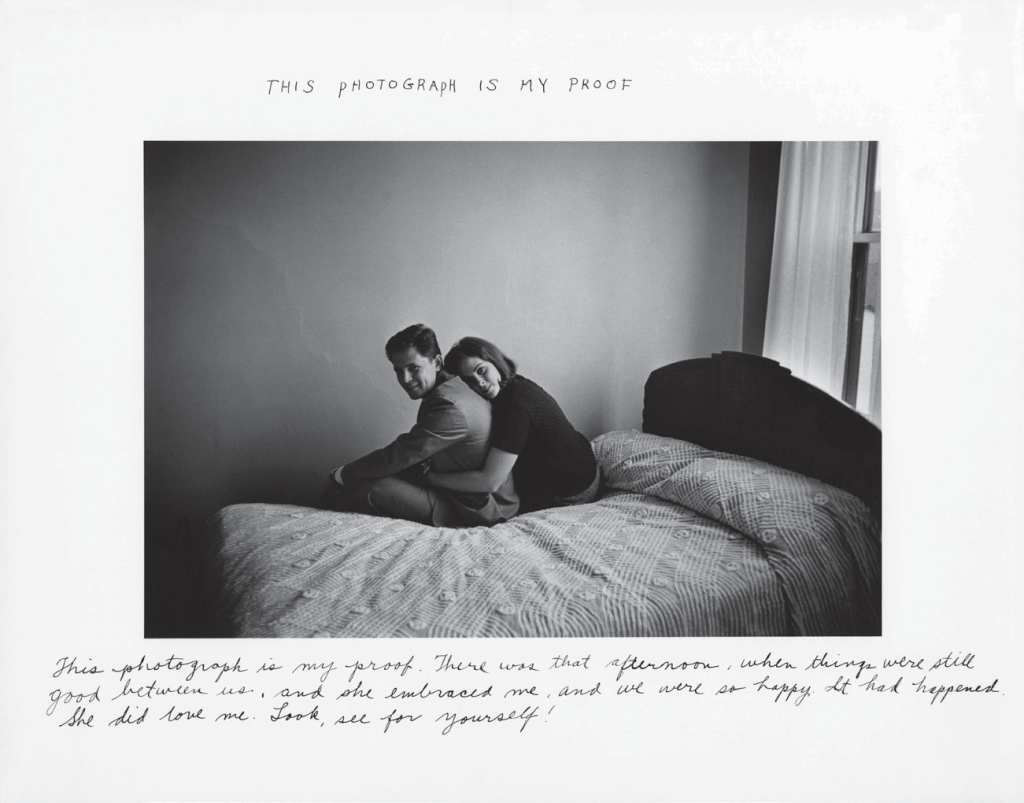

As a newbie photographer and an even newer intellectual, I was both fas- cinated and obsessed with the artist Duane Michals’s work. I was particularly interested in one of his images and how it rightly called into question what we have come to believe—merely because the photograph gently, even unno- ticeably, compelled us to.

This photograph is my proof. Or is it?

Beneath the image, Michals has written the words, “This photograph is my proof. There was that afternoon, when things were still good between us, and she embraced me, and we were so happy. It had happened. She did love me. Look, see for yourself!”

This narrative suggests a broader story, or at least one that is decidedly more complex. That the relationship depicted in the image has evolved, is evolving. I always interpreted his command to “Look see for yourself!” as a reminder that the picture is a starting point—and even an invitation to look deeper—but it isn’t everything.

The connection between images and memory has been a through line in my life and in my work as an artist, too. I always had a hard time parting with pictures or pages from a magazine I’d saved that portrayed something I was inspired by or drawn to. They were fragments of a larger story that were meant to remind me: look into this; learn more; explore. And so, perhaps it follows that I became the de facto family archivist, faithfully saving, nurturing, and sharing these discrete captured moments.

Protecting the memories of those I’ve lost.

What you are about to read is the truth. My truth. My story. Or at least a critically important and central part of it. I’ve mined my memory in an effort to both illuminate and hold tight to the essence that was my father, Michael Howard Waldman, and my mother, Jessica Friedman Waldman. This is my attempt at memorializing the unique and wholly spectacular relationships I was fortunate to have with each of them.

This book is about love. And also loss. It’s about grief and growing. It’s about what it means to be a daughter and a parent and to celebrate and elevate those relationships in your life. It’s about the act of keeping the light, their light, and the light of family and legacy—what I call “lightkeeping,” if you will—and how there can be astonishing meaning and power in doing so. As an artist and photographer, I’ve looked inward and tried to harness my creativity to reimagine, diffuse, and process the still gripping grief I have carried since my dad died in a tragic accident in 1995. It’s been an enormous challenge to manage the constant and unsettling aftershocks felt in my daily life. My 2008 photographic series, Speak Memory, explored the complexity, depth, and emotion of memory. By juxtaposing color, text, slices of light, and stream-of-consciousness imagery, this body of work sought to expose personal history and truth and the dreamlike states they often take in one’s mind. The saturation, depth, and luminance of memory reverberated through each layer and montage, offering the viewer a sense of hope and discovery.

Similarly, when I embarked on writing this book more than fifteen years ago, I was still searching for relief. For a long time, the writing was intermit- tent and inconsistent, but when the words came, they served their purpose, and mightily so. During those bursts of writing, I’d allow myself to dip back down into the depths of the missing and the longing. And then, several times a year, on birthdays or anniversaries, I’d sometimes share excerpts of my writ- ing on social media. I found the reaction and support for that still raw and exposing expression to be staggeringly helpful. And so, I continued to reveal my struggles, access my memories, and write my truth as it came to me, out of order, with no chronology. Deeply felt but disconnected. Clear as day and also hard to discern. In shades of gray or sometimes in full-blown Technicolor. Unnerving, encouraging, long ago tucked away. So very beautiful. Often inspired by a photograph rediscovered or by a brief, evocative moment, scent, or taste that unlocked countless memories.

Over time, and then with my mother’s death in 2019, I began to see how essential and fortifying it can be to examine the world outside the frame of the images in my archives—both as a way of exploring and sometimes reconstituting my memories and also very much as a way of cherishing, honoring, and shining light on my parents’ lives.

One Response